I first entered Northern Iraq in April of 1991, right after the first Gulf War, which aimed to dislodge Saddam Hussain’s forces from Kuwait, a small country he invaded the previous year.

From 1975 to 1990, Saddam’s forces had killed at least 150,000 Kurds in Iraq, and destroyed over 4,000 towns and villages.

In 1988, Saddam dropped chemical weapons in the eastern city of Halabja, killing thousands. And yet, despite the blatant war crimes, President Bush and America’s allies continued to support Saddam so he could fight a proxy war against Iran for America.

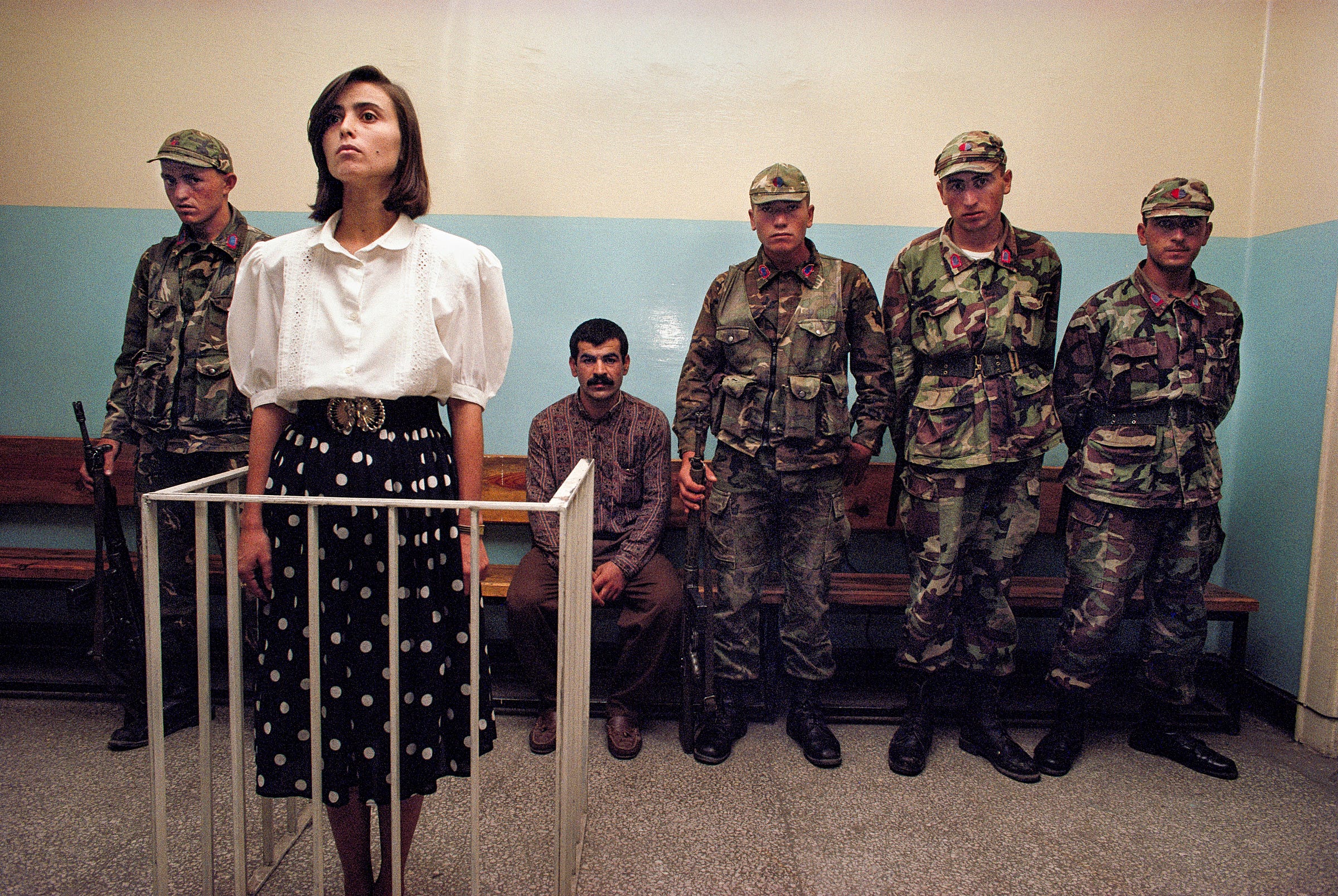

These truths were laid bare for me to witness when I hiked over the Zagros mountains from Turkey to Iraq to enter the land of my parents for the first time. I slept in rough, burned out buildings with the Kurdish Peshmerga, the traditional Kurdish warriors who had been outgunned by Saddam’s forces for so long, but could now properly begin to protect their own people.

I entered villages and towns where literally every structure had been bombed into rubble. I would return multiple times to northern Iraq to continue working on this project and what I witnessed only strengthened my heart and resolve to do this work.

The fallout from Saddam's invasion of Kuwait was one of the few positives from that war for the Kurds in Iraq.

President George HW Bush responded to the images of Kurdish refugees stranded in the mountains bordering Turkey and Iran by creating a “no fly zone" along with America’s NATO allies. It was my first real impression of the power of the American military to do good.

The US created a safe haven for a people who were coming out of a 15-year genocidal campaign by Saddam against them, provided food and water for hundreds of thousands of stranded Kurds who were now returning from the spontaneous refugee camps that Turkey and Iran set up, and helped create local governing councils so Kurdish people could begin rebuilding their villages, towns, cities and lives.

My project on the Kurds was, at that point, my most challenging work and life experience yet. It was my first time entering a war zone, and traveling through and photographing countries that were not so friendly to Americans and journalists.

Communication was not something you could rely on or even expected to have – there were no cell phones. Once you were in the field, you were alone. I made due with once-a-week scratchy long-distance calls to either my girlfriend or my editor back in Washington, DC.

Journal writing and sending postcards to friends and family helped keep me grounded and connected when away for long periods of time. Nights were not filled with downloading images and inputting metadata. Instead, I would hang out with my fixers, play backgammon for hours, read books, and explore.

For all we’ve gained through the digital revolution, we’ve lost so much of our humanity – the connections that are made by face-to-face encounters and restful sleep!

Nights in the field are now extended by hours of work. While I love the workflow of the digital age, I miss more calm and mindful nights of sleep.

Over the decades I’ve returned multiple times to work on other projects in the region, including a personal project on the invasion of Iraq in 2003, stories for National Geographic on water problems in the Middle East and Iraqi Kurdistan, and most recently to produce a film and photo essay on Syrian refugee youth in 2013.

Just this past May I returned to Northern Iraq to conduct a photography workshop with The Raw Society, and it was an absolute joy to see the progress that the Iraqi Kurds have made in rebuilding their society, communities, and economy. While seeing all those cranes in Erbil, the massive amount of new construction, a vibrant street life and good vibes everywhere we went would lead anyone to think all was well, I came to understand from talking to local folks that the corruption and other endemic problems, like in so many other places in the world, made the situation more complicated that a cursory glance would reveal.

Nonetheless, to return to a place that thirty years earlier was a destruction zone and to now see Kurdish people revitalized, thriving, with a culture that was now allowed to be taught to new generations, and a modern society in many ways that is more open, tolerant and relaxed than so much of the Middle East, was beyond my expectations. In a moment where so much of the world feels in turmoil and out of balance, it’s refreshing to see a place that is rebuilt and looking towards a future that is full of hope and warmth. As outsiders, we were greeted only with open hearts and welcoming spirits. I would encourage anyone to visit this peaceful and beautiful part of Iraq.

Photos and text: Ed Kashi.

Thank you for a great article! What a project! Sort of puts taking photos of my cats into perspective ;-).

Thank you for these insights into your earlier photographic life and those of the Kurds. Especially interesting for younger photographers, who only know the digital age, is the reflection on more peaceful nights to pass, as the films had to be send by post to the next lab. However, sleeping peacefully is difficult to imagine in so desolate, war-torn places.