It was a cold, bright November morning when our redeye touched down in Athens.

We were early. Too early for the Airbnb man to let us into our apartment, so we dragged our suitcases for coffee and a club sandwich. Our usual online recce had brought us to the artistic neighborhood of Exarchia. Or that's how it was described. As we turned the corner into the main square, we were met by half a dozen coppers dressed head-to-toe in riot gear. Their gas masks and shields glistened in the morning sun. I didn't think much of it at the time. My hometown team, Brighton & Hove Albion, were due to play AEK Athens a few days later. So, I put it down to match day preparations.

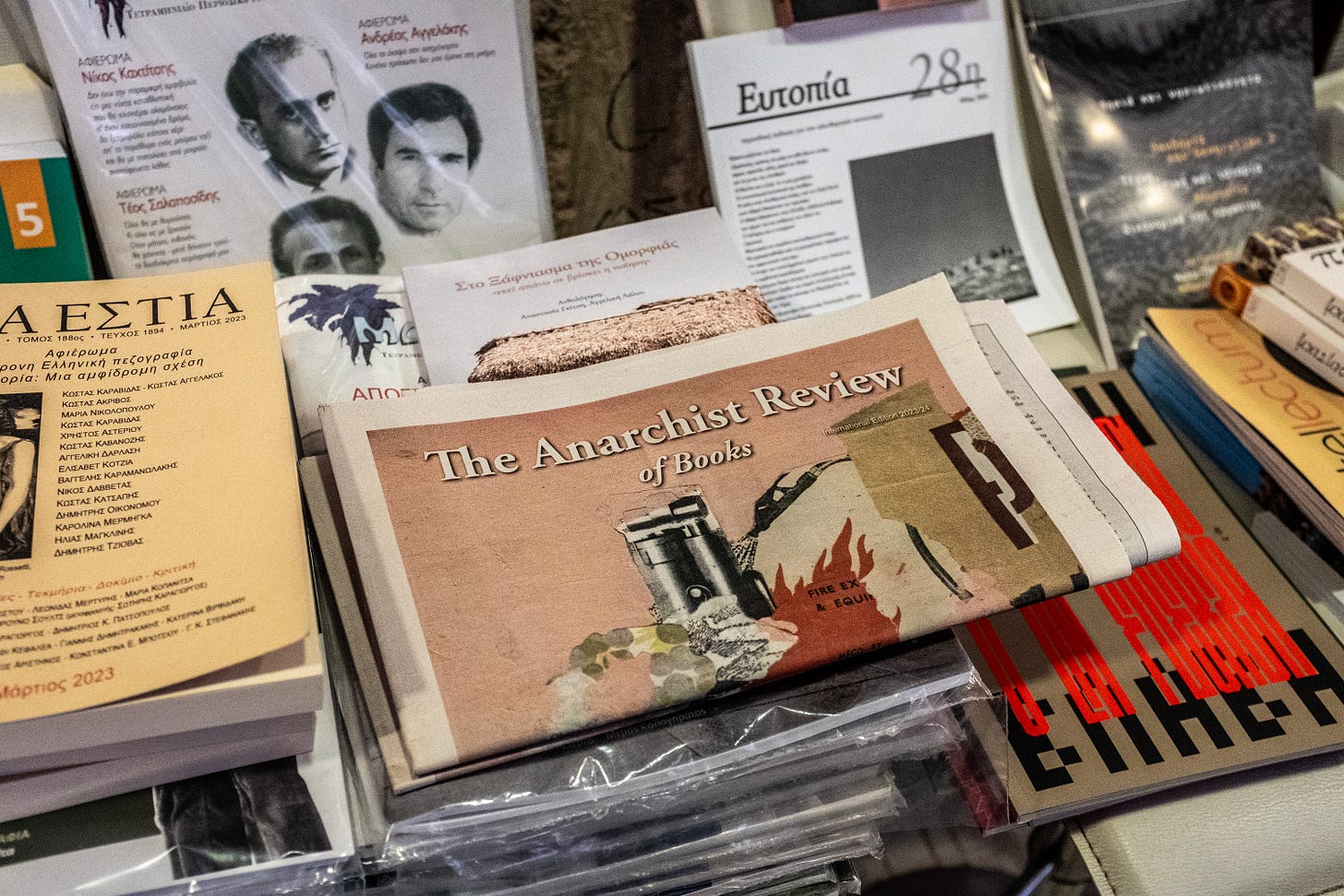

At first glance, our new surroundings are rough and ready - just how I like it. The square itself is boarded up. But the cafes and shops are busy selling books, vinyl, and art supplies. And something was giving the neighborhood a countercultural vibe.

One thing that draws me into a new place is the graffiti. It gives me a sense of what matters most to the people. The slogans in this area are vehemently anti-authority and political. Could I be reading the voice of the voiceless in the cradle of democracy? As I photograph the writing on one of the many walls, a retired journalist strikes up a conversation and gives me the lowdown. For the last fifty years, Exarchia has been the spiritual home of the Greek anarchist movement. And it is popular with artists, intellectuals, and politically active types. Until quite recently, the neighborhood was a police-free zone. So why are they here now on street corners, night and day, with seemingly nothing to do?

My knowledge of anarchy was sketchy. The Sex Pistols' debut single introduced me to the word as a two-year-old. But I was too young to get my head around its meaning. Since then, social commentators and news reports have filled in the blanks. By associating the term with violence and disorder or using it as a pejorative, they gave it negative connotations. But that might be where perception and reality shake hands and say goodbye because my first experience of anarchist territory is a neighborly willingness to help. I say this because, despite being outsiders, we get into frequent and friendly small talk, are offered free food at the market and in shops, and get a knock on our door from someone offering to take our rubbish out.

Anarchism comes from the Ancient Greek word anarkhia, which means "without a ruler", and dates back to the 5th century BC. The philosophy has some social credibility in modern Greece. After political corruption scandals, economic collapse, and austerity measures, I can understand why. At its core, anarchism combines an ethical commitment to extend liberty to everyone with a skepticism for the justification of authority. The practicalities depend on how idealistic or pragmatic an individual might be. But most anarchists want to live without the coercion and control of top-down power. To that end, they seek more freedom and independence, so that decisions are made by the people they affect. David Graeber1, the man who told me my job was bullshit and set me on the road to a photographic life, called it democracy without government. He thought anarchism was more aligned with our instincts because, for most of human history, that is exactly how we lived.

This principled resistance to authority can cause friction. Those with an anarchist mindset want more autonomy and responsibility. But the rich and powerful do not want to give up control. This dynamic and the location of Athens Polytechnic have made Exarchia a gathering point for political protest. Demonstrations and marches sometimes escalate or get hijacked by troublemakers, as happened during our stay. It felt very run-of-the-mill. People seem to know the routine. Shopkeepers roll down their shutters. The angrier protestors vandalize property. And the police bring out the tear gas. Things get back to normal within a few hours. And the day's events are forgotten almost as quickly as those anarchist ideals.

On an evening photo walk, I took what I thought was an innocuous shot of someone preparing a banner. But the person in the frame, fearful of repercussions, asked me to delete it. Photography in Exarchia is more challenging than in other parts of Athens. Graffiti saying, "Our struggle is not your entertainment", or variations to that effect are his case in point. But some revolutions will be photographed. A nearby exhibition showed us why the riot police we met on day one were there, on guard at a barricaded Exarchia Square. The government has given the go-ahead for a new Metro station with a plan to convert the community's only open space. The site has been cleared for construction, and the police are there to prevent interference. Residents are up in arms. Frustrated by the lack of consultation, many say it's a political attempt to gentrify and dismantle their anarchist enclave. But the resistance is strong, and legal challenges are ongoing.

It's another instance of this area's long-running struggle with the authorities. In 1973, students from a nearby polytechnic protested the military dictatorship and mandatory conscription. The state responded with force, killing many. And in 2008, a special officer murdered a 15-year-old boy after a verbal altercation. The incident sparked riots across Greece and deepened local resentment towards the police. The acronym ACAB adorns many walls and maybe a few knuckles, too. The graffiti and street art blend this animosity with solidarity for those in need. But, it seems to me all the vitriol and vandalism only fuel the stereotype. Maybe it represents the feelings of a discontented demographic rather than a call to arms. Like that Pistols' debut in which Johnny Rotten screamed his anarchist allegiances. Only to admit later that he used the word because it rhymed with antichrist and was never actually one himself.

But more genuine artistic overlaps do exist. Pablo Picasso flirted with the idea enough for the French Secret Service to put him under surveillance for 40 years. Oscar Wilde wrote an essay advocating for it and said he was "something of an anarchist", and one of the pioneers of our craft saw it as a peaceful way of life. In an interview with Charlie Rose, Henri Cartier-Bresson referred to his anarchism frequently, describing it as an ethic, an attitude, a way of behaving, acting, and loving. And in the introduction to his book The Mind's Eye, he wrote this:

"As far as I am concerned, taking photographs is a means of understanding which cannot be separated from other means of visual expression. It is a way of shouting, of freeing oneself, not of proving or asserting one's originality. It is a way of life. Anarchy is an ethic."2

For some anarchists, art is not only an element of a good life. But also, a means to attain it. Anarchy encourages self-actualization through personal liberation. It does not wait for permission, play to an audience, or concern itself with the commercial consequences. All these traits are necessary for making good art and, by extension, good photographs.

Photographs and writing by Ben Rook. For more of his work, check out his Substack and website.

David Graeber (1961-2020) was an American anthropologist, anarchist activist and the author of Bullshit Jobs (2018).

Charlie Rose 07/06/2000. A brief conversation with Richard Avedon, then a discussion with photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson in Paris. Rebroadcast on 08/05/2004. https://charlierose.com/videos/19739

Great write-up Ben! Sounds like an interesting place!

Great essay and photos, Ben. I definitely agree with "anarchy in photography", not sure about life.

But thanks for the link to the terrific conversation with Cartier-Bresson (Charlie Rose).